Reading DeLillo’s White Noise in the Summer of Ferguson

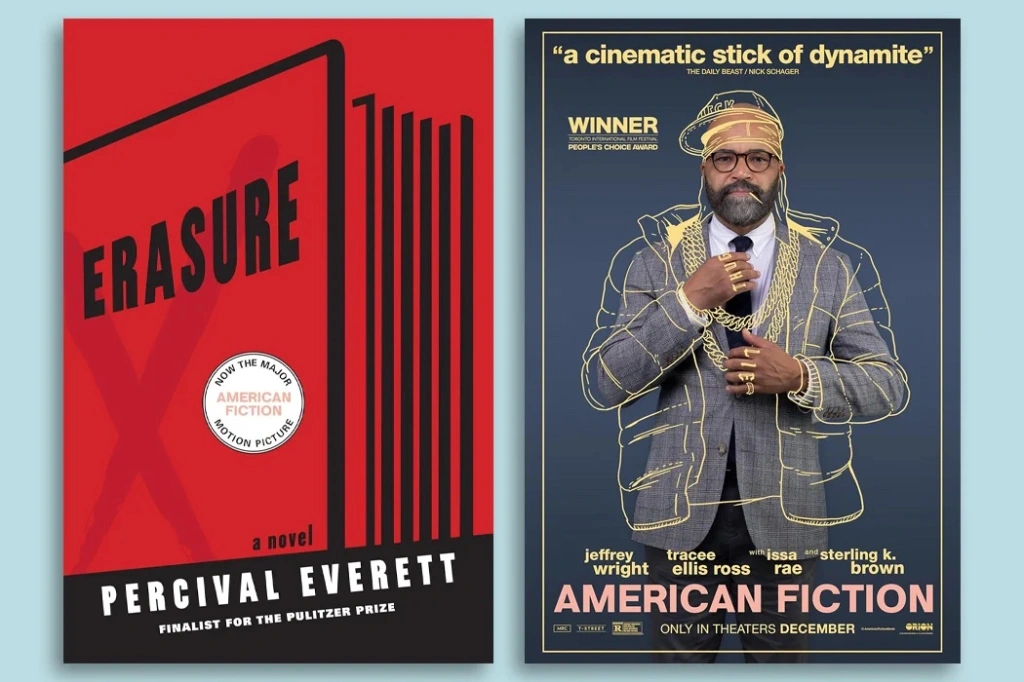

This summer I endeavored to knock a few books off the old “should-have-read-it-a-long-time-ago” list. Don DeLillo’s White Noise is one of those academic novels that I’ve name-dropped plenty of times before, but still had not read. So, in early August, comfortably ensconced in my new digs in Jersey, I sat down and dug into it. A couple weeks later, just before the start of the semester, I found myself assigned to teach a course on Contemporary American Fiction. I quickly assembled a syllabus that included White Noise and leaned heavily toward academic novels, including The Human Stain, On Beauty, Erasure and Open City. (OK, Open City may not be an academic novel exactly, but I’m hoping that reading it again will help me decide).

While reading White Noise, I was also keeping up with the escalating situation in Ferguson, Missouri after the killing of Mike Brown on August 9. Like so many other folks on Twitter I watched what started as a steady stream of tweets by people on the ground in St. Louis turn into a national and international story.

When I came to the end of Section II of White Noise – the infamous “Airborne Toxic Event” chapter – I immediately noticed correlations to what I was watching unfold on social media. The main character of White Noise is Jack Gladney, professor of “Hitler Studies” at the College-on-the-Hill. (Gladney can’t read or speak a lick of German, by the way). Jack, his fourth wife Babette, their three kids, along with their neighbors, have been evacuated from their suburban homes because of a train car spill that has left a mysterious toxic cloud hovering in the area. Section II ends with the family in a building in nearby Iron City, housed with other evacuees. A man with a small, portable TV set walks around the building and goes on an epic tirade about the media and how it has neglected their plight:

Don’t they know it’s real? Shouldn’t the streets be crawling with cameramen and soundmen and reports? Shouldn’t we be yelling out the window at them, ‘Leave us alone, we’ve been through enough, get out of here with your vile instruments of intrusion’…What exactly has to happen before they stick microphones in our faces and hound us to the doorsteps of our homes, camping out on our lawns, creating the usual media circus? Haven’t we earned the right to despise their idiot questions? (162)

Is this not exactly how things went down in Ferguson? First there was an outcry that mainstream media was neglecting the story. But once that mainstream media arrived, and acted like its obnoxious mainstream media self, then came the outcry for the reporters to leave. The media spectacle produced one particularly indelible image of CNN’s resident black pathologist Don Lemon, surrounded by a group of St. Louis residents giving him mad side-eye.

In fact, the media mess got so bad that journalist Ryan Schuessler voluntarily left the scene, and poignantly explained his reasons for doing so, citing the arrogant selfishness of the talking head divas who parachuted in and immediately started throwing their weight around.

In my class I assigned part of Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s The Anxiety of Obsolescence to read along with the novel. Chapter 3 of the book, “Spectacle,” is specifically about DeLillo’s work, and Fitzpatrick uses some noteworthy media theorists (Postman, McLuhan, Baudrillard, among others) to pick apart the media critique in the novel (while also remaining suspicious of how discourses of obsolescence deployed by straight white male writers are too often imbued with specific racial and gender politics). One of the great things that White Noise does so well is to show the discomfiting ways televisionized populations have come to rely on mainstream media narratives to validate their suffering. From the Airborne Toxic Event, to the people on a terribly turbulent plane ride that managed to make it to the ground unscathed, the novel shows characters repeatedly turning to television news to narrate and give meaning to their own traumatic experiences.

This is a particularly dangerous game for black folks when corporate media is as hostile to black life as it is. (Yes, even that so-called “liberal” media who covered the event deflected conversations away from the injustice of a police murder and toward tired, insulting debates about sagging pants and black parenting). That media attention is a terribly recursive loop that is difficult, maybe even impossible, to escape. Attracting national attention was absolutely essential to the growth of the Ferguson movement and has resulted in an international outcry against the Ferguson police and their malicious mishandling of both the shooting and the protests. (Their hostility and incompetence are not even up for discussion). At the same time, Don Lemon and the rest came swooping onto the scene with their “idiot questions” about black behavior, because they know those hot-button topics will generate the predictable ratings numbers and page views that they need to satisfy their advertisers.

White Noise is also a novel that begs to be read through the critical lenses of race and class privilege. In my own classroom it took a while for students to get around to it – I’m getting better at shutting up and letting them talk things through on their own – but eventually, they hit the key points about race and class that were staring us all in the face. Clearly these characters are folks whose anxieties, fears and consumption habits are not universal, but are directly related to the level of comfort and privilege that they take for granted. When the cloud first forms, and before they ever considered having to evacuate, Jack Gladney says:

These things happen to poor people who live in exposed areas. Society is set up in such a way that it’s the poor and the uneducated who suffer the main impact of natural and man-made disasters. People in low-lying areas get the floods, people in shanties get the hurricanes and tornadoes. I’m a college professor. Did you ever see a college professor rowing a boat down his own street in one of those TV floods? We live in a neat and pleasant town near a college with a quaint name. These things don’t happen in places like Blacksmith. (114)

That passage conjured images in my mind of the horrors of the 5th ward during Hurricane Katrina, and the projects in Red Hook and Coney Island during Hurricane Sandy (among many other unfortunate scenes). I noticed some early reviewers of White Noise cited the Bhopal disaster in India, which happened in December 1984, just a few weeks before the novel hit bookstores in 1985. Bhopal was a real live Airborne Toxic Event, except there were no fancy microbes to clean up the air, and people are still living with the after-effects of the company’s callous negligence some 29 years later.

But I now think about the story of David Hooks– a 59 year old white man in Georgia – who on September 24 was killed by DEA agents who barged into his house with a no-knock warrant. No drugs were found.

Surely such things only happen to people in the hood who voluntarily choose to live around drug dealers, right? Surely such things do not happen to polite law-abiding white citizens, do they? As the Ferguson story grew, white nationalists found a cause celebré in Darren Wilson, raising over a half million dollars (to date) for his legal defense (and, apparently, for lap dances and beers, at his discretion). But more level-headed white folks have (hopefully) looked at the body armor and tanks and tear gas on the streets of Ferguson and have realized that the urban militarism deployed against the protesters there won’t stay confined to the hood for long. Hopefully they realize now (if Occupy Wall Street didn’t show them before) that all those chickens that people have warned about – perpetual wars in other places leading to escalated militarism in police forces domestically – have indeed come home to roost.

For the most part our conversations about White Noise in class didn’t get this politically topical. Again, I tried to stay out of the way and let them think their own way through it. We did talk about race, religion, class and gender. But they also spoke quite eloquently about the age of television and how televisual media has come to dominate our self-perception. They talked about fear of death in the novel (one of its biggest topics given the whole storyline with the experimental drug Dylar that Babette is taking to quell her death fears), and I was proud to hear them deal with a such a heavy and discomfiting topic with maturity, intelligence and humor.

Consumerism was another one of the big themes we lingered on. There’s a lot of shopping in the book. DeLillo eschews the pastoral in favor of the bright, sterile artificiality of shopping malls and supermarkets. In one rapturously written scene set in a massive shopping mall DeLillo writes:

We moved from store to store, rejecting not only items in certain departments, not only entire departments, but whole stores, mammoth corporations that did not strike our fancy for one reason or another. There was always another store, three floors, eight floors, basement full of cheese graters and paring knives. I shopped with reckless abandon. I shopped for immediate needs and distant contingencies. I shopped for its own sake, looking and touching, inspecting merchandise I had no intention of buying, then buying it. I sent clerks into their fabric books and pattern books to search for elusive designs. I began to grow in value and self-regard. I filled myself out, formed new aspects of myself, located a person I’d forgotten existed. Brightness settled around me. (83-84)

Here then, is the 21st century. Maybe it has always been this way. On one side of town an unarmed black teenager takes six bullets to the body and the head from the gun of a policeman, his lifeless corpse left to rot in the street for hours afterward, the officer who shot him filing no report, and charged with nothing. Meanwhile, on the other side of town people go from store to gleaming store, shopping for cheese graters and paring knives, feeling good about themselves and their comfortable lives. The dread of White Noise, the dread that the shoppers try to placate with their shopping, is that maybe the boundary between these two sides of town is far more permeable than they want to admit, or imagine.

—

DeLillo, Don. White Noise. New York: Penguin, 1985.

Fitzpatrick, Kathleen. The Anxiety of Obsolescence: The American Novel in the Age of Television. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2006.