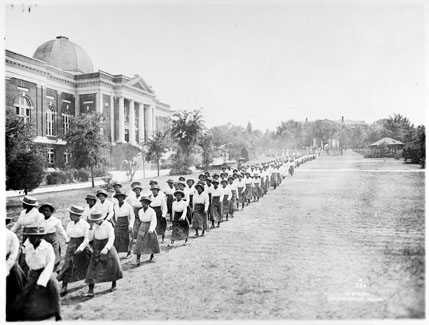

Women students of Tuskegee Institute marching in rows on campus, c. 1910s (from The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture http://digital.nypl.org/schomburg/images_aa19/toc.html )

I wasn’t really satisfied with what I wrote in my last post, so I decided to put together some more informal thoughts on finishing the degree.

In my previous post I said I avoid the “grad school advice” conversations, but that’s not really accurate. The truth is, I give graduate school advice all the time, and I’m willing to have that conversation with anyone who wants to have it. Giving this kind of counsel is part of my job as a professor. I work as an adjunct now, and in an adjunctified higher education system, I can’t tell my students to go have those conversations with their “real professors.” We’re the only “real professors” that our students are going to get most of the time, and that means being involved in all sorts of informal academic and career advisement, including writing recommendations and serving as references. And if I’m eventually fortunate enough to land a position where I advise graduate students, I’ll have these conversations with them as well. I’m far from the first person to point this out: we academics are now in the awkward position of having to discourage students from following in our footsteps. We can’t in good conscience tell them that there will be adequate jobs with adequate pay if they enter the profession now.

That said, I also agree with Tressie McMillan Cottom when she wrote that the “Don’t Go to Grad School” advice shouldn’t apply to everyone. As bad as the academic teaching market is now, college enrollments are still up, and students are still going, and there is still a dire shortage of women and faculty of color in academia. I see this reflected in the institution where I teach now, where the majority of students are black and brown. But the faculty? Well, not so much. It was a bit jarring in my first few weeks there to be repeatedly mistaken for a student when I walked into faculty spaces. And I ain’t that young anymore. That seems to happen less now that I’ve taken to wearing a jacket and tie regularly. But then that decision has led to a couple of weird encounters with an older white female colleague who seems to think that my wearing a blazer and a tie is somehow an invitation to come up to me and start patronizing me about my clothes and then complaining about the style of dress and habits of the students (again, most of whom are black and brown). Remember, I’m from Mississippi, so I’m well-schooled in the ways of white folk when it comes to pitting black folks against each other. Her unsolicited comments reminded me why I always count the Battle Royale scene in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man among the most powerful literary allegories for black politics in America.

What I really meant to say in that last post is that I tend to stay away from conversations about grad school advice online. Conversations in this medium tend to devolve into arguments with pompous douchebags bloviating about “choices” and “supply and demand” and “the market.” And, just as often, those conversations also involve listening to academics whose politics I mostly agree with, but who also portray themselves as pious, innocent victims in a way that I’m not entirely comfortable with either. Maybe I don’t want to be that innocent. Maybe I really did “get over” by going to grad school. Maybe I like the fact that academia has afforded me a chance to do work that I actually enjoy doing (some of the time) instead of working at some soul-sucking job that I hated (all of the time). And maybe even with some debt and terrible job prospects, the Ph.D. has put me into a career that has, thus far, allowed me to live peaceably with the world, particularly given my own less-than-outgoing personality. Maybe, unlike some of my colleagues whose families are littered with advanced degrees, it means something to me to be the first Ph.D. in the family. Maybe I figured out, from experience, that all work sucks anyway (ALL.OF.IT.) and that work is a curse (hey, it even says so in the bible, Genesis 3:17-19), and so I’d rather work at something in the long run that gives me some pleasure and meaning in my life, even if it means making a little less money and being a little less respectable in the eyes of my hot-shot corporate classmates from undergrad who are making five times more than I ever will.

I went into this with very different personal expectations about what kind of life I would have with a career in academia, particularly going into English. I figured that for me, the house-car-2.5kids-retirement-in-Florida thing probably wasn’t going to happen anyway, and that I probably live more frugally now than most people are willing to live. I’ve scraped through with adjunct jobs and walking tours, and not everyone can do that. And I also happen to be the kind of queer who identifies with the old school queers who saw getting off the path of respectability as one of the benefits of queer life, instead of all these gay assimilationists now who want to get married and be monogamous suburbanites. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that!)

I’ve also been the beneficiary of sheer dumb luck. I happen to have parents who have remained financially stable and healthy into their later years. (A teacher and a mechanic used to be able to do such things in America). I don’t have children to provide for, or other family members in dire need of support. It’s just the roll of the dice. One catastrophe could have changed all that. I say this because I hate listening to pretentious jerkoffs giving advice to other people without taking into consideration that other people may not be leading such a charmed existence, and might have responsibilities which limit the sacrifices they can make for their profession. I’ve been able to be responsibly irresponsible only because I haven’t had those kinds of responsibilities forced upon me by the circumstances of life. Getting the Ph.D. was a calculated gamble, and there’s still the possibility I could lose big. And there are times when I do regret not being able to do certain things for my family that I might have been able to do had I gone into a different line of work. But I don’t regret the last few years either. I’ve been able to do the kind of research and writing and intellectual engagement that I’ve wanted to do, and I do believe that I’ve put myself in a position to do more interesting and worthwhile projects that will pay off in the future. But there are no guarantees.

I also know how to distinguish my own individual reasons for going into academia from the bigger picture about the academic labor system. The professoriate in the American higher education system is sickeningly exploited through and through. From the conversations I’ve had with my own students about adjuncts, I know that few of them even knew what an adjunct was before I told them. Now they know. And every student who comes through any class of mine will always know, because they deserve to know the truth about their own educations, and because this should be a part of their political literacy.

So, yes, I always advise people to tread carefully when it comes to grad school, but I don’t always say “don’t go.” That’s the irony I was going for with the theme of “over-education” in my dissertation. As black folks we’ve been “over-educated” since the first ones of us learned to read and write. And as of now, there are nowhere near enough black PhDs and professors to tell black students not to pursue a career in higher education. (The same goes for other minority groups as well.) Even some of those white academics you see online snarking about academia are at least lobbing their insults at the academy with degrees in hand. And I’d even say that to students from all backgrounds. Maybe academia really is the right fit for you if you’re passionate enough about it and willing to fight for it, and if you can find a way to do it responsibly without bankrupting yourself.

Yes, it’s a tough racket, and it will probably mean not living like a baller. And if you have family obligations, you do have to take those into consideration. And yes, you do have to be careful because your love for your discipline and your commitment to teaching and your loyalty to your students WILL be abused by the institutions you work for again, and again, and again, and you need to be prepared to push back against that abuse when it’s necessary.

My grad school advice is more along the lines of Charles Bukowski’s advice in “So You Want to be a Writer.”

if it doesn’t come bursting out of you

in spite of everything,

don’t do it.

unless it comes unasked out of your

heart and your mind and your mouth

and your gut,

don’t do it.

if you have to sit for hours

staring at your computer screen

or hunched over your

typewriter

searching for words,

don’t do it.

if you’re doing it for money or

fame,

don’t do it…

It shouldn’t have to be this way. It shouldn’t take that kind of reckless sacrificial commitment to be a teacher. I wish we lived in a culture where the citizenry actually supported education and believed it was worthwhile to pay educators a fair wage, instead of believing in the cynical politicians who have turned teachers and professors into boogeymen. I wish the institutions that hire us now actually gave us the resources to do the jobs that we are asked to do, instead of expecting us to go above and beyond as the norm. But that’s not our reality right now.

I also know that the situation will never change without people getting involved on the inside, doing whatever we can in order to try to create something different, by whatever means are necessary. Sometimes you really do have to be in the game to change the game.

Hey, Lavelle! I enjoyed your words. I’m glad that you’re trying to change the system and that you’re in the system to do that. I wasn’t brave enough to stay in academia. I took my degree and ran. I applaud you for your thoughtful decision to make it work. I feel hopeful for higher education!

Good for you Megan! I see you’ve got your business up and running. I suppose I shouldn’t speak too soon. I don’t have any full-time offers yet, and realistically, having seen how some of my friends have struggled in this market, they may never come. That’s a possibility. I’m also exploring other options outside of academia too. Sarah Kendzior has written about this as a “post-employment economy” and I’ve found that a wonderfully clarifying term. It’s great to hear from you!

Good Morning Lavelle. My colleague and Facebook friend Claudia highlighted this piece and I am so glad she did. Your words really resonate with me on many levels. As a woman of color, I, too, am often mistaken by staff at my school as a student, and treated rudely I might add. And I am definitely NOT young any more.

The status of teachers in our society reflects the inner corruption and decay at its core. Teaching at LaGuardia, I have had the privilege of teaching students from all over the world. Students from numerous countries treat me so well and show me so much respect because they are taught in their societies to honor and revere their teachers. The students raised in America — not so much. It is this attitude of disrespect that has created the corporate-influenced climate that has bred the exploitative and pernicious educational system that you refer to, where someone like yourself with so much education and so much to offer students has to “scrape by.” I hope that you do land a full-time position soon and that academia doesn’t lose you. That would be a shame.

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment. I’m a little surprised at how many people have read this.

Yes, there is a certain resentment about educators that is endemic to American students, and I think you’re right about the political culture that encourages it. That’s why I find it is important to engage in these conversations and tell it like it really is. It’s amazing that even with all the information available online about the real academic labor market, you still have people reproducing this tired culture wars rhetoric circa 1992 that tenured radicals with huge salaries are somehow running higher ed. Anyway, thanks for the good wishes.

Congratulations, Lavelle!

Hey, thanks Alex!