1. The 2001 HBO film Wit, based on the play W;t by Margaret Edson, is a somber, cerebral film that follows the final days in the life of Dr. Vivian Bearing as she undergoes aggressive treatments for advanced ovarian cancer. An English professor who specializes in the Holy Sonnets of 17th century English poet John Donne, Bearing is depicted as a meticulous, exacting scholar and a stern, uncompromising teacher in the classroom. While in the hospital she is attended to by one of her former students, Jason Posner, who took a course with her as an undergraduate and found it surprisingly helpful in his preparation for clinical research.

I’ve been thinking about Wit in relation to Kevin Dettmar’s Atlantic article from about a year ago “Dead Poets Society is a Terrible Defense of the Humanities,” in which he delivers a scathing critique of the beloved film, and accuses it of trafficking in the “sentimental humanities.” I’ve written about Wit before, placing it at the top of my 2010 list of Academic Films, and mostly I still stand by that ranking. After seeing the Atlantic article I wanted to put down some more specific thoughts about how Wit is a different, and perhaps more nuanced, depiction of poetry, the humanities and education.

2. I know I should just say what I have to say about Wit, and keep myself out of this. But I also feel compelled to make legible the difficulties of writing as a teaching-intensive academic. The way I see it, I have two options: I can post these incomplete, imperfect thoughts about Wit now, or I can set all of this aside once more, losing it in the cluttered mental activities of teaching, writing, job searching and traveling that await me in the coming weeks.

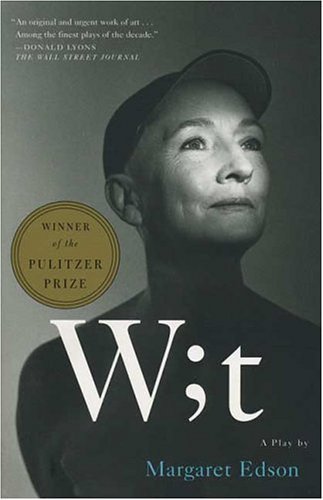

3. There is always more reading to be done. Must one read everything before one writes anything? In preparation to write this I flipped through the Cambridge Companion to John Donne (alas, only one mention of Wit) and Donne: Poetical Works, edited by Herbert J.C. Grierson (the best collected poems copy available in the WPUNJ library), re-watched parts of the 2001 HBO Film featuring Emma Thompson (I’ve screened it in composition classes for the past two years), and re-read the play version, which is actually titled W;t with a semi-colon.

4. About that semi-colon: W;t was the original title of the Margaret Edson play on which the film is based. The title refers to a flashback scene to her graduate school days where we see the future Dr. Bearing in the office of her graduate school mentor Dr. E.M. Ashford who is chastising Vivian for having written her research paper using an edition of Donne’s “Death, be not proud” that Ashford believed to be improperly edited and punctuated. As she tells Vivian: “Your essay on Holy Sonnet Six, Miss Bearing, is a melodrama, with a veneer of scholarship unworthy of you – to say nothing of Donne. Do it again”

Ashford argues that the last line of Donne’s poem had been improperly rendered as:

“And Death shall be no more; Death thou shalt die!”

When in fact it should have read as:

“And death shall be no more, Death thou shalt die.”

Ashford’s quibble over the “hysterical” punctuation of the corrupted version – a semi-colon instead of a comma, a capital d in the first clause where death is not personified or addressed directly, and the exclamation point at the end – exemplifies the meticulous eye for scholarship that she passes on to Vivian, who tries to pass the same scholarly precision on to her own students. I have no idea whether there is any actual debate over the punctuation of that line in the poem, though the Westmoreland manuscripts that Ashford references in the film are real. Nevertheless, the scene is a rare moment of serious textual scholarship presented in an academic film.

5. Dettmar insists that Dead Poets Society propagates the destructive idea of humanistic education as the “sentimental humanities,” which he describes as “humanities content stripped of all humanities methodology and rigor,” and which perpetuate the idea that “the humanities is easy, a soft option; that humanities doesn’t train thinkers.” One of his key examples for this comes from an early scene in the film:

“When his students first sit down with their new poetry anthology, Keating tricks a student into reading aloud a few sentences from the banal introduction written by Dr. J. Evans Pritchard, PhD – a cartoonish version of academic criticism that opens with a split infinitive! – before instructing them to tear those pages out of their books.”

The scene is a stark, violent contrast to Wit’s careful dissection of Donne’s poem. Dettmar goes on to write:

“What Keating (Robin Williams) models for his student’s isn’t literary criticism, or analysis, or even study. In fact, it’s not even good, careful reading. Rather, it’s the literary equivalent of fandom. Worse, it’s anti-intellectual.”

It’s obvious why people love this film. Keating is vibrant, engaging, and passionate, the sort of teacher who brings literature to life. I imagine the film’s fiercest defenders hearken back to their own high school classes with boring English teachers who made them slog through Beowulf and Shakespeare, and who treated literature like bitter medicine that their students must swallow in order to grow into well-rounded, intelligent persons.

You might say these films are the proverbial apples and oranges. Dead Poets Society is about stimulating an enthusiasm for reading and learning in high school kids, whereas Wit is about sharpening and refining those sensibilities into rigorous scholarship at the college level. Perhaps. But the films also represent two different, though not entirely mutually exclusive, approaches to literature, the fannish sentimentality of falling in love with poetry that Keating encourages in his students, and the more difficult work of expressing that love in the careful, scholarly attention depicted in Wit.

6. Death stalks us all, certainly. I’ve wanted to write something about Wit and that Dettmar article for months. (I found at least three different printouts of the article scattered in my folders from false starts.) In the interim, my writing plans were hampered by two notable deaths related to these works: Robin Williams, the star of Dead Poets Society, who tragically took his own life last summer, and Mike Nichols, director of Wit, who died at age 83. Both were famous, beloved artists. In a culture of celebrity, sorry to say, some deaths mean more than others. To say that #AllDeathsMatter is just as false in its universality as #AllLivesMatter. Some deaths resonant more in the public, are more highly amplified. But, as Wit aims to teach us, death also remains the great equalizer. Time eventually washes us all away.

7. Early in the play Vivian assures the audience that she is an expert on these weighty matters: “I know all about life and death. I am, after all, a scholar of Donne’s Holy Sonnets, which explore mortality in greater depth than any other body of work in the English language.” Yet, later in the play, as the treatments intensify, and after a tough conversation with the nurse Susie Monahan about her end-of-life options, Vivian takes a different tone. “We are discussing life and death, and not in the abstract either: we are discussing my life and my death…” Having a discussion about whether the doctors should resuscitate you if your heart stops has a way of putting a finer point on things.

8. I remember those previous lines from the film, but reading them in the play version, the dialogue continues. There, Bearing says “we are discussing my life and my death and my brain is dulling, and poor Susie’s was never very sharp to being with, and I can’t conceive of any other…tone.” The lines are part of a scene in which she softens and recognizes how much she needs the kindness and compassion that Susie provides to her (and which her student Jason does not), but Bearing also comes off as condescending and mean toward Susie by implying that she is dull. Overall, she’s not a very likeable protagonist. A colleague who saw the original production on stage told me that she found the character in that production even more abrasive than Emma Thompson’s version in the film where, yes, she seems pretentious and self-important, but ultimately comes off as endearing in her flaws.

9. Gender is one of the most glaring differences between Dead Poets Society and Wit. In Dettmar’s essay he identifies a strain of macho anti-intellectualism running through Keating’s approach to reading. The scholarly introduction by Pritchard is meant to invoke a preening, emasculated version of criticism. In a later scene Keating has the boys going all native, gathering outside in an Indian cave to read poetry together out in nature, white boys reading literature in red-face, appropriating a kind of native “savagery” to recuperate their masculinity and avoid becoming faggoty uptight intellectuals like Pritchard.

Wit, on the other hand, is one of few academic films to pass the Bechdel Test with flying colors. The scene in Ashford’s office alone is remarkable. Yet, there is something troubling about Bearing’s loneliness. She has no partner or sexual life to speak of. From the scene where Posner takes her medical history we glean that she is unmarried, with no children, and not having any sexual relations. Maybe she’s a lesbian? It’s not clear from the play, though the fact that the playwright is an out lesbian makes that a possibility, though not a certainty. There is a feminist consciousness about her. She’s certainly aware of what it means to be a woman in the academy. But hers is not a sexy, Having-It-All, Leaned-In sort of feminism. What she represents is the tough, personal sacrifice that women often had to make, and still have to make, to play “the man’s game” in academia. Things are a little bit better now, but academic women still find themselves having to strategize about family planning, speculating whether male (or female) advisors will question their devotion to the profession when they have kids in the early stages of their careers. They have to wonder how their parenting choices, hairstyles, body type and style of dress will cause them to be judged in job searches, concerns that their male counterparts only think about if they are conscientious enough to even pay attention to such things at all. (That’s called privilege, folks.) As I stated in my academic film list, Wit is a welcome alternative to all those academic novels about male professors in mid-life crises, and it’s the rare work of academic fiction that allows women to be seen as serious scholars, neither obsessed with man-hunting, nor naïve to the gender inequalities around them.

10. I noticed that one commenter on Dettmar’s article ridiculed what I actually thought was one of the best sentences in the essay: “The power of literature is the power of alterity, creating the possibility of encountering the other in a form not easily recuperable, not easily assimilable to the self.” This! I mean why else would have a bunch of immigrant kids or MTA motormen or nurses or fast food workers from the 5 boroughs (or the New Jersey suburbs) reading the words of a 17th century Anglican priest and watching a play about a professor of English poetry? Yes, reading is about encountering something outside of the self, of getting into another person’s thoughts or into another culture, or a constructed fictional world, and trying to understand it. I will always believe that this kind of reading is worthwhile for students of all classes, races, genders and professions.

11. A recent Chronicle of Higher Education article traces the political disdain for the humanities back to Ronald Reagan’s 1967 statement that taxpayers shouldn’t “subsidize intellectual curiosity.” STEM fields are often pitted against the humanities when people insist that the ultimate aim of the university lies in job training and increased earning potential. The dissolution of public funding and rising costs of college education put pressure on students to seek the greatest return on a risky investment. Hit any online message board on this subject and you will find a plethora of snarky comments mocking the art history major with $80,000 in student loans.

I also keep coming back to Tressie McMillan Cottom’s argument that the emphasis on “training” in higher education ignores the reality of the job market itself, and that what is needed is a federal job guarantee to ensure that there will be any kind of employment awaiting 21st century college graduates, regardless of degree. It’s a salient point given that even STEM graduates are finding themselves underemployed, and the tech economy that we are all supposed to be preparing to work in is a field full of janky fly-by-night startups and low-wage freelance labor that offers little in the way of benefits or long-term potential.

12. W.E.B. Du Bois’s arguments about “The Talented Tenth” and the classical versus industrial education model, and his debates with Booker T. Washington over the direction of black education at the turn of the 20th century, are all well-known. But less appreciated is the extent to which Du Bois understood this struggle as one that would have implications in American higher education policy far beyond The Negro Question. In that essay on “The Talented Tenth” he wrote:

“The problem of training the Negro is to-day immensely complicated by the fact that the whole question of efficiency and appropriateness of our present systems of education, for any kind of child, is a matter of active debate, in which final settlement seems still afar off.”

And he also wrote that:

“School houses do not teach themselves – piles of brick and mortar and machinery do not send out men. It is the trained, living human soul, cultivated and strengthened by long study and thought, that breathes the real breath of life into boys and girls that makes them human, whether they be black or white, Greek, Russian or American.”

Again, and again in Du Bois’s writing, one encounters his insistence that what happens to blacks in American education (and politics) will have a profound effect on the country as a whole.

13. In Wit, Jason Posner makes the case that the complexity of Donne’s poetry was great preparation for clinical research, and that Dr. Bearing’s rigorous approach to poetry was not in dreamy sentimentality, but in hard-nosed intellectual work that sharpened the mind.

Susie: She [Vivian] is not what I imagined. I thought somebody who studied poetry would be sort of dreamy, you know?

Jason: Oh, not the way she did it. It felt more like bootcamp than English class. This guy John Donne was incredibly intense. Like your whole brain had to be in knots before you could get it.

Susie: He made it hard on purpose?

Jason: Well, it has to do with the subject. The Holy Sonnets we worked on most they were mostly about Salvation Anxiety. That’s a term I made up in one of my papers, but I think it fits pretty well. Salvation Anxiety. You’re this brilliant guy, I mean, brilliant—this guy makes Shakespeare sound like a Hallmark card. And you know you’re a sinner. And there’s this promise of salvation, the whole religious thing. But you just can’t deal with it.

Susie: How come?

Jason: It just doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. But you can’t face life without it either. So you write these screwed-up sonnets. Everything is brilliantly convoluted. Really tricky stuff. Bouncing off the walls. Like a game, to make the puzzle so complicated.

Susie: But what happens in the end?

Jason: End of what?

Susie: To John Donne. Does he ever get it?

Jason: Get what?

Susie: His Salvation Anxiety. Does he ever understand?

Jason: Oh, no way. The puzzle takes over. You’re not even trying to solve it anymore. Fascinating, really. Great training for lab research. Looking at things in increasing levels of complexity.

I admit I’ve found this argument compelling, and I’ve tried to use it to make the case with my own students that the humanities will help them become better thinkers, and more attractive to employers in other industries. I’m not sure I completely buy this utilitarian argument for the humanities, but I sell it to get them to read the work. Certainly I believe the mental work that they do in writing classes will help them to become better communicators regardless of their fields.

And yet, there’s that romantic part of me that believes in the aesthetic value of art in itself, that art is indeed “useless” in the crass materialistic terms in which it is forced to be quantified, and that its “uselessness” is the very thing that makes it a potent form of resistance against the material forces that destroy the human spirit, and that humanities need not be bullied into justifying itself to suits who never gave a damn about it anyway. At the same time there are material necessities: computers and classrooms and buildings and archives that require money. And as a scholar of African-American studies, I’m not so much of a romantic that I can ignore the importance of institutionalizing knowledge in order to preserve and legitimate it, particularly for undervalued and marginalized fields like my own.

14. I recently discovered some rather insightful blog posts on Wit by Robin Bates on his blog Better Living Through Beowulf. I wish that I’d seen these when I was teaching the play. I’ve leaned on some of these posts while writing this piece, and all of the entries are worth taking time to read.

Bates actually proposed a question that I put to my own students: “Can Donne Help Us Cope With Death?” More specifically I asked my students to write about the ways in which Donne’s poetry does, and does not help Vivian through her last days in the film. On the blog there’s a lively exchange between Bates and a commenter about this very aspect of the play. The commenter argues that the end the play seems to shuck Bearing’s scholarship and intelligence in favor of sentimentality, particularly in the scene where Ashford visits her in the hospital when she is very ill and has difficulty speaking. Ashford climbs up on the bed, embraces Vivian as she weeps, and asks Vivian if she wants her to recite some Donne. In response, Vivian groans out a “nooo…” (The answer usually gets a chuckle when I’ve shown it in class). Instead Ashford picks up The Runaway Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown, a book that she’s just bought for her grandson, and reads it to Vivian, noting that the story of the little bunny running away from his mother is an allegory of the soul: ‘No matter where it hides, God will find it.”

One can read that scene and interpret it as an ultimate rejection of Donne’s poetry, that it is inadequate for Vivian when the chips are really down. However, the students and I agreed that Donne’s poetry does help her in life. It gave her purpose as a scholar, provided her with stimulating intellectual challenges. It gave a platform to teach her students how to think through the toughest problems that life with throw at them. And when she was diagnosed, it helped her to be brave and face the treatments, and helped her to realize that that just as her own scholarship on Donne had contributed to the academic knowledge among her peers, her suffering and endurance as a cancer patient would be a contribution to the knowledge of medical research, and perhaps might help other women find treatments for ovarian cancer.

I read that scene not as a wholesale rejection of the intellectual, but as something akin to Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers song “Be With Me Jesus” a prayer meant for the moment of transition, when yes, one might want to cling to something more sentimental than the intellectual swordplay of abstract theology:

Oh Lord,

The time is growing nigh

When I must breathe

My last breath and sigh

Lord in my dying hour

Stay with me Lord

15. Though it is never mentioned directly in the play or film, Donne’s most well-known prose work, Meditation XVII, seems an important subtext. It speaks to Vivian’s loneliness and independence, and the transition to dependency that she makes in the hospital.

Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? But who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world? No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or thine own were. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

I also had my students write about Meditation XVII in relation to the play. Vivian, the reclusive, intellectual loner finds herself in a place of insecurity and dependence upon others, even upon people whom she looks down upon as her inferiors.

Speaking of how humanities can be of social benefit, I think of our current debacle over measles outbreaks and vaccinations. This seems like a moment where we might want to dust off Meditation XVII, or maybe even the old-fashioned Enlightenment ideal of Rousseau’s Social Contract. We are afflicted by an aggressive individualism that obscures the myriad ways that every single one of us – at least the ones of us who do NOT live like the Unabomber in an off-the-grid shack in the woods – is, in fact, always already interdependent upon the kindness, intelligence, labor and sacrifice of other people.

16. In Samuel Delany’s 1988 memoir The Motion of Light in Water, he tells an anecdote from his younger days when his wife, the poet Marilyn Hacker, was accosted on the street by TV news reporters looking for quotes on an evening news bit and asked why she wanted to be an artist in the age of science.

“I don’t really see much difference between them,” Marilyn answered, into their lenses through hers. “Both are based on fine observation of the world.”

17. I think about E.M. Ashford’s instructions to Vivian on how to read “Death be not proud,” as a model for thinking about the humanities as whole. To study the arts and letters, even perhaps to read them with that “perfect contempt” from Marianne Moore’s “Poetry”, one can learn from, and be enlarged by, humanistic studies. In this case, Ashford insists that even careful attention to the syntax of a poem can be an invitation to ponder the greatest mysteries of life and death.

Nothing but a breath—a comma—separates life from life everlasting. It is very simple really. With the original punctuation restored, death is no longer something to act out on a stage, with exclamation points. It’s a comma, a pause.

This way, the uncompromising way, one learns something from this poem, wouldn’t you say? Life, death. Soul, God. Past, present. Not insuperable barriers, not semicolons, just a comma.

FURTHER READING:

–Margaret Edson’s Wit – An Audience Guide

-This series of posts about Donne and Wit on the Better Living Through Beowulf blog are worth reading in detail:

“Arguing over Life, Death, and a Semicolon”

“Can Donne Help Us Cope With Death”

“The Limitations of Cerebral Teaching”

“Doctors, Bad Bedside Manners, and Poetry”

“Don’t Underestimate Your Students”

-A New York Times article on Margaret Edson and the 2012 Broadway production featuring Cynthia Nixon.

This is a great post, Lavelle, and I love the form. This gave me a lot think about — thank you!

Thanks Kristina! I feel like it’s a bit uneven. I may come back and take another shot at it when I teach the play again.